Mental Science

Image credit: Weird Science

An essay on what can be measured, and what can't...

Buddhist meditation and cognitive sciences

By Daniel Simpson

"The first world is the objective world of things. The second world is my inner subjective world. But, says Popper,1 there's a third world, the world of objective contents of thoughts..." - Colin Wilson,2 sampled for The Orb's "O.O.B.E."3

Cosmic chat (via Mind & Life)

On my first trip to Dharamsala, the Indian home of Tibet's exiled leaders, a fellow backpacker urged me to read The Tao of Physics.4 Its mystical hybrid of scientific findings and Eastern teachings sounded dull. Back then, I preferred taking drugs to blow my mind. Who cared if what the Buddha may have said could be compared to quantum theory? As it happened, a group of people down the road: the Dalai Lama had just hosted a conference on this theme with foreign scientists. Their exchange began 10 years earlier, with the inaugural gathering of the Mind & Life Institute.5 Last year marked the thirtieth. Although these discussions are often intriguing, they appear inconclusive; more like interfaith dialogue than conversion either way. Nonetheless, they have helped spur research on how meditation works, and on the ways it changes brains.

The involvement of Buddhists with science dates back to colonial occupation. Long before Queen Victoria became Empress of India in the 1870s, Christian missionaries denounced Asian religions as unscientific, unlike their own "true faith", shared by Isaac Newton. Buddhism barely existed as a concept: the term was "constructed", to quote Donald Lopez, by 19th century Western scholars.6 Chief among them was Eugene Burnouf, a professor in Paris who never visited Asia but read lots of texts, discerning a "human Buddhism" that "consists almost entirely in very simple rules of morality"7 and a psychology "of incontestable value for the history of the human spirit."8 Hearing this, some Buddhists got inspired: it offered a template for how to define themselves. Sri Lankan modernisers turned Christian criticism upside down, saying Theravada Buddhism was not a religion but "a science of the mind."9

This argument, based on meditative insights found in early Pali texts, distanced Buddhism from ritual. Echoing a Westernised view of the Buddha as social reformer, who challenged Brahmin power like Martin Luther did the Pope's, Sri Lankans such as Dharmapala critiqued the Buddhism practised in villages as degraded. This appealed to the urban middle classes, whose education in English had instilled Western values yet left them subservient. Effectively, says Richard King, "the colonial discourse of the British became mimetically reproduced in an indigenous and anti-colonial form."10 At a debate in Panadura in 1862, Buddhist scholars and monks said it was really Christianity that was riddled with fantastical inconsistencies, and at odds with science. They won hands down. In Geoffrey Samuel's opinion, the defeated Westerners were "perhaps escapees from oppressive or conflicted Christian backgrounds" and "happy to collaborate in an enterprise which promised both to relativise the Church's claims to authority and to provide a new, more acceptable moral basis for contemporary life."11

The notion of Buddhism as applied mental science spread with lay meditation. Nationalists in Thailand, Sri Lanka and Burma encouraged practice outside monasteries, legitimised with reference to texts that foreign Orientalists had translated.12 Japanese Buddhism was also reshaped in this Western reflection, as the Meiji Empire flexed its muscles.13 The latest cross-cultural fusion is the Mind & Life Institute. The brainchild of two Western Buddhists (a neuroscientist and a businessman), it serves as a platform for the 14th Dalai Lama, who has fought since the 1950s to end China's military occupation of Tibet. Courting Western support, he aims to change the image of Tibet's esoteric form of Buddhism, which Europeans once scorned as "Lamaism".14 Mind & Life provides a vehicle for doing this. Its first proceedings were published with the subtitle: "Conversations with the Dalai Lama on the Sciences of Mind".15

Some aspects of the Dalai Lama's worldview seem more malleable than others. Although revered as a voice of non-violence, he declined to condemn the invasion of Iraq in 2003, deeming it "too early to say" if pre-emptive war on a falsified pretext was a bad thing, presumably mindful, says Bernard Faure, of "the risk of offending his allies in the United States government."16 As casualties mounted, he stuck to his guns, declaring: "At least the motivation is to bring democracy and freedom."17 Only late in 2006 did he concede: "things not very positive" with "too many killings".18 Realpolitik guides his thinking about a successor. He has suggested there might not be one, having devolved his political role to an elected leader.19 China, meanwhile, plans to divine his reborn form by traditional means within its borders. As Lopez notes: "The implication of politics in the discourse of Buddhism and science has been ironically clear in recent years."20

In conversations with scientists, traditional views are less negotiable, despite suggestions to the contrary. "One fundamental attitude shared by Buddhism and science is the commitment to deep searching for reality by empirical means," the Dalai Lama writes, "and to be willing to discard accepted or long-held positions if our search finds that the truth is different."21 This has limits. At the first Mind & Life symposium, the physicist Jeremy Hayward said: "scientists take the view that consciousness arises from a material cause," to which the Dalai Lama countered: "Buddhists cannot accept this."22 Recalling the method by which he is said to have reincarnated, he asked participants to: "Imagine a person, a Tantric practitioner who actually transfers his consciousness to a fresh corpse," clarifying that "in this case, you see, he has a completely new body but it's the same life, the same person."23 A footnote underlines that "His Holiness in fact appears to have meant that consciousness is transferred by meditative practices" as opposed to suggesting "there is a brain transplant".24

This fundamental difference has dogged proceedings ever since. In 2005, 544 brain researchers signed a petition urging the Society for Neuroscience to disinvite the Dalai Lama from its annual meeting. "We'll be talking about cells and molecules," objected Jianguo Gu at the University of Florida, "and he's going to talk about something that isn't there."25 In response, one of Mind & Life's translators, Alan Wallace, called the petitioners "zealots" and emphasised many had Chinese ancestry.26 The Dalai Lama "has said time and again that he would reject the Buddhist assertion of reincarnation if positive scientific evidence is produced that refutes it," Wallace protested. "Are mainstream scientists equally empirical and rational, allowing them to give a fair hearing to evidence and reasoning that are inconsistent with their materialistic assumptions?" At Mind & Life events, at least, they hold their tongues.

In Geoffrey Samuel's assessment, "much of what happens in this process is less a dialogue between equal systems of thought than an assimilation of the more 'acceptable' elements within Tibetan and Buddhist thought into an essentially Western context."27 One Mind & Life scientist, Richard Davidson, has bent over backwards to avoid causing offence while defending materialism.28 He acknowledges being asked "sharply but respectfully" by the Dalai Lama to "distinguish between that which has been empirically confirmed and that which is simply assumed and has become part of our theoretical and conceptual dogma."29 Yet he feels obliged to note that "certain scientific assumptions are themselves based on well-established principles," adding (via the circumlocution "some would say") that: "the dependence of mind on brain is one such assumption that has been subjected to countless empirical tests, and each and every one of them has provided support for this general claim."30

As the Dalai Lama sees it, science can never answer every question. Its remit is the first of the Buddha's Noble Truths: that life leaves us unsatisfied.31 Science "examines the material bases of suffering," he writes, "for it covers the entire spectrum of the physical environment - 'the container' - as well as the sentient beings - 'the contained'." A subsidiary focus is mental, "the realm of psychology, consciousness, the afflictions, and karma," where "the second of the truths, the origin of suffering" is located. Yet "the third and fourth truths, cessation [of suffering] and the path [to attain it], are effectively outside the domain of scientific analysis in that they pertain primarily to what might be called philosophy and religion."32

BRAINS IN HATS

This outlook has led to a focus on cognitive science, as ways to scan brains get more revealing. Of course, scoffs Samuel: "no amount of brain-scanning of meditating yogis will either prove or disprove Madhyamika philosophy"; or whether the Buddha foretold relativity, quantum physics or Big Bang theory.33 Neuroimaging spawns papers in journals and wide-eyed reporting, as when Matthieu Ricard, a French Buddhist monk, was dubbed "the happiest man in the world" on account of activity observed in his left prefrontal cortex.34 Ricard thought this "flattering", an interviewer wrote, "given the tiny percentage of the global population who have had their brain patterns monitored by the same state-of-the-art technology."35 The title stuck.

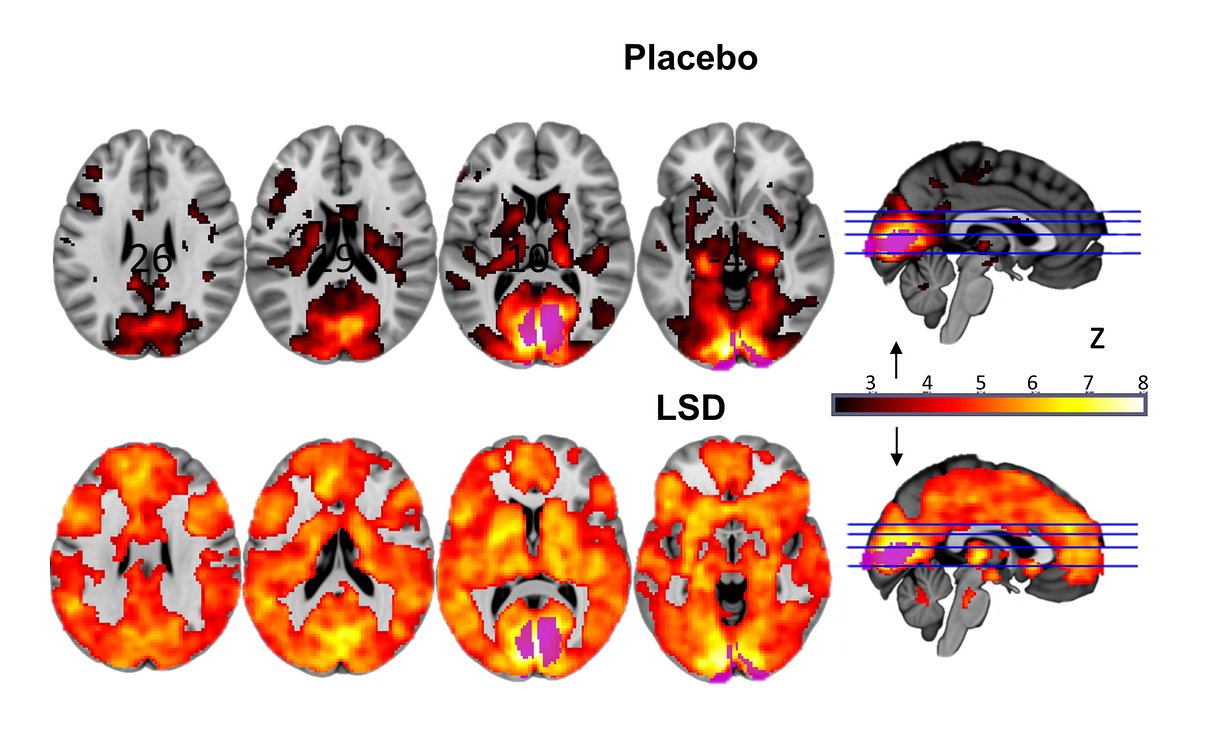

It remains unclear what such things teach us. Not all Buddhists meditate, but some have done so for more than 2,000 years. Others have compiled extensive texts on theory. Something must have occurred behind their eyes, and it seems less arcane when displayed on screens. However, as the philosopher Jay Garfield notes: "Despite all of the glitzy powerpoints and breathless rhetoric" from fellow Mind & Life participants, "neuroimaging results are much ado about what we all should have known already."36 Basically, "pictures show that the brain does something when the mind does something."37 Similarly, publishing: "Neural correlates of the LSD experience revealed by multimodal neuroimaging" cannot communicate what acid feels like.38 The Guardian said: "lots of orange," referring to snapshots of the scans.39 Even if science were to map every state known to expert meditators, we would still need to practice ourselves, unless someone made drugs that induced the effects, which may include many not seen by a scanner.

Your brain on acid (via Imperial College London)

Another source of confusion is internal. As Garfield reminds us, brains have filters, and a lot of what they do is unconscious.40 "At a more fundamental level - the deeper, non-introspectible level," he writes, "information is cognitively available" but "actively suppressed before reaching surface consciousness." Hence, even the most skilled meditators cannot perceive unfiltered truth, such as gaps in our vision that the brain fills in. "If the doors of perception were cleansed," mused William Blake, "every thing would appear to man as it is, infinite."41 Yet to dwell in that state might have drawbacks. It could be hard to do ordinary tasks if we "see a World in a Grain of Sand / And a Heaven in a Wild Flower."42 Hallucinogens can feel overwhelming; the orange in LSD scans means more parts of the brain do visual processing, though this is often a dream-like "seeing with eyes-shut".43 Although the mind senses more stimulation, cortical activity drops and other networks show "decreased connectivity", correlating to "ego-dissolution" and "altered meaning".44 Direct perception can be both misleading and enlightening. Or as a tripping Dutch hippie once told me: "Life is an illusion, choose a nice one."

What scientists study depends on equipment. To generate data their peers might approve, something has to be measured. For meditation, this began with electroencephalography (EEG), which first recorded brain oscillations in 1929, and found rhythmical patterns in sleep and such conditions as epilepsy. Observing neuron synchrony across different brain parts, researchers identified slower alpha and theta waves (4-13 Hz) and faster beta and gamma frequencies (above 15 Hz). By the 1950s, portable machines allowed for fieldwork. Early teams looked at Indian yogis in samadhi, defined as a state in which "the perfectly motionless subject is insensible to all that surrounds him and is conscious of nothing but the subject of his meditation."45 The results were striking: accelerated alpha activity, especially in experienced meditators, whose faster rhythms fell in frequency and amplitude, with generalised beta and gamma waves in deep concentration.46 Others in Japan did related work with Zen practitioners. Findings are hard to compare, but suggest high-amplitude gamma waves could indicate states of clarity, and that "alpha/theta oscillations during Zazen or Samadhi practices differ functionally from the alpha/theta activity during a relaxed non-meditative state."47

The same cannot be said for what the Beatles learned in India, from the self-styled Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. His Transcendental Meditation (TM) became a popular fad and was studied in depth in the 1970s. Although its goal is an elevated state called "cosmic consciousness",48 it seems straightforward: sit down, shut your eyes and repeat a sound, without trying to concentrate. Or as John Lennon put it, before being taught: "Turn off your mind, relax and float downstream..."49 This lyric was borrowed from a book about LSD,50 which claimed to be based on an ancient Buddhist text, although The Tibetan Book of the Dead was the work of a Theosophist from New Jersey, combining manuscripts he got in Darjeeling with teachings from Egypt.51 TM mantras sound equally dubious. They currently cost $1,500,52 yet a review of historical studies finds: "Other relaxation techniques have led to the same EEG profile," while "the initial claim that TM produces a unique state of consciousness different from sleep has been refuted."53 A filmmaker got himself scanned while reciting his mantra, and again while repeating a random German word, which relaxed him more.54

Early research on TM's effects was mostly positive, which helped the Maharishi build a business empire.55 The most rigorous study appeared in 1975, using a randomised double-blind process with a placebo. Control participants got TM instructions, but no mantra: after six months of practice they were just as relaxed as TM meditators.56 The organisation continued unfazed, churning out its own studies. As for its claims to spread peaceful vibrations with "yogic flying" (cross-legged hopping on mattresses), its biggest donor has doubts. After giving TM more than $100 million, the publisher Earl Kaplan called it the "biggest spiritual scam in modern history," hawking a "mechanical and repetitive" technique "which leads to brain washing."57 Before leaving, he proposed hiring a team of devoted practitioners to change the world. "I said: 'Maharishi, why don't we just put a 10,000-group in place? I've donated enough money to support a group like that in India, and with 10,000 people you've been saying there would be world peace, right away'. Then he looked at me and he said: 'Earl, I have no idea if a 10,000-group would create world peace. We would have to create that group and see what effects it would have'..."58

GREAT UNKNOWNS

Science has yet to discover if meditation produces a state that is either unique or accessible to all. Different practices affect different people in different ways.59 To contribute to finding out more, the Dalai Lama sent a fax to the Mind & Life scientist Richard Davidson, who recalls being offered "the Olympic athletes, the gold medallists, of meditation" for lab research.60 Most monks were reluctant at first, but inspired by Ricard (the world's "happiest man"), a few more have donned geodesic hair-nets wired with EEG sensors, and looked at pictures to test their responses. They have also spent hours trying to focus their minds in the noisy machines that do magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). From the Dalai Lama's perspective: "The goal here is not to prove Buddhism right or wrong - or even to bring people to Buddhism - but rather to take these methods out of the traditional context, study their potential benefits, and share the findings with anyone who might find them helpful."61

Some forms of science have changed his mind. He says: "empirically verified insights of modern cosmology and astronomy must compel us now to modify, or in some cases reject, many aspects of traditional cosmology as found in ancient Buddhist texts."62 By sending monks to America, he hoped to help transform other people's minds: "It seems that Buddhist explanations - particularly in the cognitive, biological and brain sciences - can sometimes give Western-trained scientists a new way to look at their own fields."63

Barely a decade ago, Davidson conceded: "the vast majority of meditation research is schlock."64 For half a century, the focus was on short-term effects on stress and related issues, effectively summarised by the term "relaxation response," which was popularised by the Harvard professor Herbert Benson, and found in multiple forms.65 Studies have since shown the benefits of mindfulness, a secularised practice drawn from Theravada Buddhism, which teaches how to distinguish one's sensory experience from the thoughts and emotions it produces. Mindfulness-based interventions have helped patients to face chronic pain, recurrent depression and anxiety, and ever more conditions are being researched.66 Many papers have repeated old problems with TM studies; inadequate controls mean: "we still can't be sure about what is the 'active' ingredient," lament Farias and Wikholm.67

The world's happiest man? (via University of Wisconsin)

Until comparatively recently, academics engaged with meditation based on texts, as opposed to experience, making it harder for scientists to grasp technical subtleties. This has changed with more scholar-practitioners and the emergence of fields addressing neuroplasticity (the ways that brains can be reshaped). Davidson and many of his colleagues are long-term meditators, yet they still feel constrained, afraid of sounding New Age. "Neuroscientists want to preserve both the substance and the image of rigour in their approach," explains Jonathan Cohen, another Mind & Life contributor, "so one doesn't want to be seen as whisking out into the la-la land of studying consciousness."68 Davidson speaks of "the conservatism and stasis of the academy", which Buddhists are eroding by drawing attention to the longer-term changes in accomplished practitioners.69 "You've helped us to focus on plasticity," Davidson told the Dalai Lama at last year's Mind & Life meeting.70 "You've shown us for example the importance of warm-heartedness," which "scientists will take away from their time here and will begin to think about how it can get translated into their own work."

Some critics are less than impressed by the West's translation of Eastern teachings. "Mindfulness in Buddhist tradition is to transform one's sense of self," stresses Ron Purser, who lampoons the "McMindfulness" taught as glorified self-help.71 "It's not about attaining personal goals attached to personal desires; the goal is to liberate oneself from greed, ill will and delusion, not to achieve stress reduction." Meditation might improve concentration skills, but does it root out the causes of suffering without an awareness of interconnectedness, and other components of "right-view"?72 It seems not from the pre-deployment training of U.S. combat troops in mindfulness: no outbreaks of non-violence have been reported from the battlefield.

What might be studied to foster "warm-heartedness"? Part of the purpose of scanning skilled meditators has been to map the "neural correlates" of compassion and other beneficial states. This could assist with reverse-engineering "Buddha's Brain", to cite the title of a paper by Davidson's team.73 We can hardwire happiness, argues Rick Hanson, an author of books on how to do this. "By knowing with increasing clarity and specificity something about what's going on in the brain when someone is in a positive or wholesome or even exalted state of mind," Hanson says, "we can use the power of the mind alone to stimulate the neural substrates underlying those wholesome states of mind and thereby strengthen them," through repeated engagement.74 Practice might still be required, but incentives are clearer; albeit unrelated to the First Noble Truth, which says that striving for happiness keeps us stuck in disappointment.

A landmark study by Davidson's lab had familiar flaws. "Individuals who trained in compassion for two weeks were more altruistic toward a victim," it announced, which "correlated with training-related changes in the neural response to suffering", suggesting "functional neuroplasticity in the circuitry underlying compassion and altruism."75 Put simply, being kind makes you kinder. Or does it? "While the meditation group focused on extremely positive emotions to counteract suffering," object Farias and Wikholm, "the control group did a rather dull task of reinterpreting a stressful event."76 There was thus no effective comparison. A more recent publication was humbler, concluding: "rigorous studies are still needed to uncover the precise mechanisms" behind "demonstrable changes" in "subjective experience, behaviour, patterns of neural activity, and peripheral biology."77

Some Buddhist ideas have scientific parallels, like the absence of self. "From a neuroscience perspective," says Evan Thompson at the University of British Columbia, "there's nothing that corresponds to the sense that there's an unchanging self."78 The whole world is in flux. "The brain and the body work together in the context of our physical environment to create a sense of self," Thompson says, but "it's misguided to say that just because it's a construction, it's an illusion." Moreover, notes Jay Garfield: "Our introspective awareness of our cognitive processes, no matter how sophisticated, is as constructed, and hence as fallible as any other perception," so reported experiences of pure consciousness may be illusory. "Perception, we learn from empirical research, is never immediate, and never devoid of inferential processes. It is guided by attention and pretension, mediated by memory and low-level inference."79

This undermines Alan Wallace's pitch for "contemplative science," which amounts to a defence of subjective experience against reductionist materialism.80 "The only instrument humanity has ever had for directly observing the mind is the mind itself, so that is what must be refined," he insists,81 because "insight into the deepest dimension of consciousness" is "the key to understanding the nature of reality".82 But if we each have our personal "reality-tunnel", how insightfully can it be shared with someone else?83 Meanwhile, modern physics already regards us as part of whatever we observe,84 and even the materialists Wallace disdains have developed a theory that "treats consciousness as an intrinsic, fundamental property of reality," which is "in line with the central intuitions of panpsychism," namely: "there is only one substance" so "matter and mind are one thing".85

For now, the distinction endures. "I think, therefore I am" is the Western way of proving life is not "a neural inter-active simulation" like The Matrix.86 Mind and body are seen as separate though related. To Wallace's frustration,87 science dismisses "nonphysical influences in organic evolution or in human affairs," despite having "no technology that can detect the presence or absence of any kind of consciousness, for scientists do not even know what exactly is to be measured".88 His critique is sound but he makes few suggestions (apart from endorsing meditation), while tempting materialists to cite Bertrand Russell's "celestial teapot" as another cosmic theory they need not disprove.89 Wallace might as well be seeking approval of Terence McKenna's view that an alien intelligence helps human evolve through magic mushrooms.90

As Lopez concludes: "If an ancient religion like Buddhism has anything to offer science, it is not in the facile confirmation of its findings."91 Its contribution is a challenge: "to understand oneself, and the world, as merely a process, an extraordinary process of cause and effect, operating without an essence, yet seeing the salvation of others, who also do not exist, as the highest form of human endeavour."92 As in The Matrix, "there's a difference between knowing the path and walking the path."93 If meditation bores you, try LSD, counsels the neuroscientist Marc Lewis.94 "We are literally small-minded most of the time," he observes, but people "turn to psychedelics to wake us up to the possibilities of a universal perspective," and the "meaning hidden behind the transitory stupidity of human strivings that lead nowhere." However one attains it, the only proof of experiential insight is what one makes of it.

--

UPDATE: Alan Wallace has responded; our exchange is uploaded here.

Further Reading

Karl Popper, "Epistemology without a Knowing Subject", Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics, Vol. 52 (1968), pp.333-373. ↩

Colin Wilson, New Pathways in Psychology: Maslow and the Post-Freudian Revolution (Chapel Hill: Maurice Bassett Publishing, 2001), p.22. ↩

The Orb, "O.O.B.E." U.F.Orb (London: Big Life, 1992). ↩

Fritjof Capra, The Tao of Physics (Boulder: Shambhala, 1975). ↩

Mind & Life Institute, "Dialogues with the Dalai Lama", online archive (accessed 10 April 2016). ↩

Donald Lopez (ed.), Curators of the Buddha: The Study of Buddhism Under Colonialism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995),p.7. ↩

Eugene Burnouf, Introduction to the History of Indian Buddhism, Translated from French by Katia Buffetrille and Donald Lopez (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), p.328. ↩

Ibid., p.27. ↩

Donald Lopez, The Scientific Buddha: His Short and Happy Life (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), p.11. ↩

Richard King, Orientalism and Religion: Postcolonial Theory, India and "The Mystic East" (London: Routledge, 1999), p.151. ↩

Geoffrey Samuel, "Between Buddhism and Science, Between Mind and Body". Religions, 5 (2014), p.561. ↩

Robert Sharf, "Buddhist Modernism and the Rhetoric of Meditative Experience," Numen, 42 (1995), pp.252-3. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Lopez, The Scientific Buddha, p.12. ↩

Jeremy Hayward and Francisco Varela (eds.), Gentle Bridges: Conversations with the Dalai Lama on the Sciences of Mind (Boston: Shambhala, 1992). ↩

Bernard Faure, Unmasking Buddhism (Oxford: Blackwell, 2009), p.75-6. ↩

Dalai Lama XIV, "The Heart of Nonviolence: A Conversation with the Dalai Lama," The Aurora Forum at Stanford University, 4 November 2005, p.5. ↩

Laura Kurtzman, "AP Interview: Dalai Lama says war in Iraq has shed too much blood," Associated Press, 27 September 2006. ↩

Pankaj Mishra, "The Last Dalai Lama?" The New York Times Magazine, 6 December 2015. ↩

Lopez, The Scientific Buddha, p.12. ↩

Dalai Lama XIV, The Universe in a Single Atom: the Convergence of Science and Spirituality (New York: Morgan Road, 2005), p.25. ↩

Hayward and Varela, Gentle Bridges, p.153. ↩

Ibid., p.155. ↩

Ibid. ↩

David Adam, "Plan for Dalai Lama lecture angers neuroscientists," The Guardian, 27 July 2005. ↩

Alan Wallace, "Finding the Middle Way," The Center for Buddhist Studies Weblog, Columbia University, posted 13 November 2005. ↩

Samuel, "Between Buddhism and Science," pp.567-8. ↩

Richard Davidson, "Science and Spirituality: Probing the Convergences and Tensions," a review of the Dalai Lama's Universe in a Single Atom, PsycCRITIQUES, Vol. 51 (28), Article 12, pp.1-5. ↩

Ibid., p.2. ↩

Ibid., pp.3-4. ↩

Dalai Lama, Universe in a Single Atom, pp.105-6. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Samuel, "Between Buddhism and Science," p.569. ↩

Anthony Barnes, "This is the happiest man in the world," The Independent on Sunday, 21 January 2007. ↩

Robert Chalmers, "Meet Mr Happy," The Independent on Sunday, 18 February 2007. ↩

Jay Garfield, "Ask not what Buddhism can do for cognitive science; ask what cognitive science can do for Buddhism," Bulletin of Tibetology, 47 (2011), p.17. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Robin Carhart-Harris et al., "Neural correlates of the LSD experience revealed by multimodal neuroimaging," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 113, No. 17 (2016), pp.4853–4858. ↩

Ian Sample, "LSD's impact on the brain revealed in groundbreaking images," The Guardian, 11 April 2016. ↩

Garfield, "Ask not what Buddhism can do," pp.19-23. ↩

William Blake, The Complete Poems (London: Penguin Classics, 1977), p.188. ↩

Ibid., p.506. ↩

Carhart-Harris et al., "Neural correlates of the LSD experience," p.4856. ↩

Ibid., p.4853. ↩

Antoine Lutz et al., "Meditation and the Neuroscience of Consciousness: An Introduction," In Philip David Zelaso, Morris Moscovitch and Evan Thompson (eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Consciousness (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), p.536. ↩

Ibid., pp.535-6. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Robert Forman Enlightenment Ain't What It's Cracked Up To Be: A Journey of Discovery, Snow and Jazz in the Soul (Winchester: O Books, 2011), p.20. ↩

The Beatles, "Tomorrow Never Knows," Revolver (London: Parlophone, 1966). ↩

Timothy Leary et al., The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead (London: Penguin Classics, 2008), p.6. ↩

Donald Lopez, The Tibetan Book of the Dead: A Biography (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011). ↩

Maharishi Foundation USA, TM Course Fee (accessed 14 April 2016). ↩

Lutz et al., "Meditation and the Neuroscience of Consciousness," p.536. ↩

David Sieveking (dir.), David Wants To Fly (Berlin: Neue Visionen, 2010) ↩

Miguel Farias and Catherine Wikholm, The Buddha Pill: Can Meditation Change You? (London: Watkins Publishing, 2015), pp.52-3. ↩

Ibid., pp.56-8. ↩

Earl Kaplan (2004). "The Truth," letter to TM practitioners in Fairfield, Iowa, 16 April 2004. ↩

Sieveking, David Wants To Fly. ↩

Farias and Wikholm, The Buddha Pill, pp.213-8. ↩

Stephen Hall, "Is Buddhism Good for Your Health?" The New York Times Magazine, 14 September 2003. ↩

Dalai Lama XIV, "Our Faith in Science," The New York Times, 12 November 2005. ↩

Dalai Lama XIV, "Science at the Crossroads," based on a speech at the Society for Neuroscience in Washington DC, 12 November 2005. ↩

Dalai Lama XIV, "The Monk in the Lab," The New York Times, 26 April 2003. ↩

Hall, "Is Buddhism Good for Your Health?" ↩

Adam Smith, Powers of Mind (New York: Random House, 1975), pp.151-2. ↩

Lutz et al., "Meditation and the Neuroscience of Consciousness," p.521. ↩

Farias and Wikholm, The Buddha Pill, p.217. ↩

Hall, "Is Buddhism Good for Your Health?" ↩

Dalai Lama XIV, "Mind & Life XXX - Session 8, Dalai Lama," recording of a conference on Perceptions, Concepts and Self - Contemporary Scientific and Buddhist Perspectives, Sera Monastery, Karnataka, 17 December 2015. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Anne Kingston, "Mindfulness goes corporate - and purists aren't pleased," Maclean's, 21 April 2013. ↩

Paul Fuller The Notion of Ditthi in Theravada Buddhism: The Point of View (London: Routledge, 2005), p.77. ↩

Richard Davidson and Antoine Lutz, "Buddha’s Brain: Neuroplasticity and Meditation," IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, January 2008, pp.172-6. ↩

Rick Hanson, "The Intersection of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Contemplative Practice," audio excerpt from The Enlightened Brain, 19 August 2015. ↩

Helen Weng et al., "Compassion Training Alters Altruism and Neural Responses to Suffering," Psychological Science, vol. 24, no. 7 (2013), pp.1176-7. ↩

Farias and Wikholm, The Buddha Pill, p.135. ↩

Cortland Dahl et al., "Reconstructing and deconstructing the self: cognitive mechanisms in meditation practice," Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Vol. 19, No. 9 (2015), p.521. ↩

Olivia Goldhill, "Neuroscience backs up the Buddhist belief that 'the self' isn't constant, but ever-changing". Quartz, 20 September 2015. ↩

Garfield, "Ask not what Buddhism can do," p.27. ↩

Alan Wallace, Contemplative Science: Where Buddhism and Neuroscience Converge (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007). ↩

Ibid., p.51. ↩

Ibid., p.60. ↩

Robert Anton Wilson, Prometheus Rising (Tempe: New Falcon Publications, 1983), p.171. ↩

Carlo Rovelli, Seven Brief Lessons on Physics, translated from Italian by Simon Carnell and Erica Segre (London: Allen Lane, 2015), p.72. ↩

Giulio Tononi and Christof Koch, "Consciousness: here, there and everywhere?" Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B, Vol. 370, Issue 1668 (2015), p.11. ↩

The Wachowski Brothers (dir.), The Matrix (Burbank: Warner Bros, 1999). ↩

Alan Wallace, The Taboo of Subjectivity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), p.25. ↩

Ibid., p.3. ↩

Bertrand Russell, The Collected Papers of Bertrand Russell Vol. 11: Last Philosophical Testament 1947-68 (London: Routledge, 1997), pp.547-8. ↩

Terence McKenna, True Hallucinations: Being an Account of the Author's Extraordinary Adventures in the Devil's Paradise (New York: HarperCollins, 1993), pp.210-2. ↩

Lopez, The Scientific Buddha, p.123. ↩

Ibid., p.132. ↩

Wachowski Brothers, The Matrix, 1999. ↩

Marc Lewis, "What LSD tells us about human nature," The Guardian, 15 April 2016. ↩